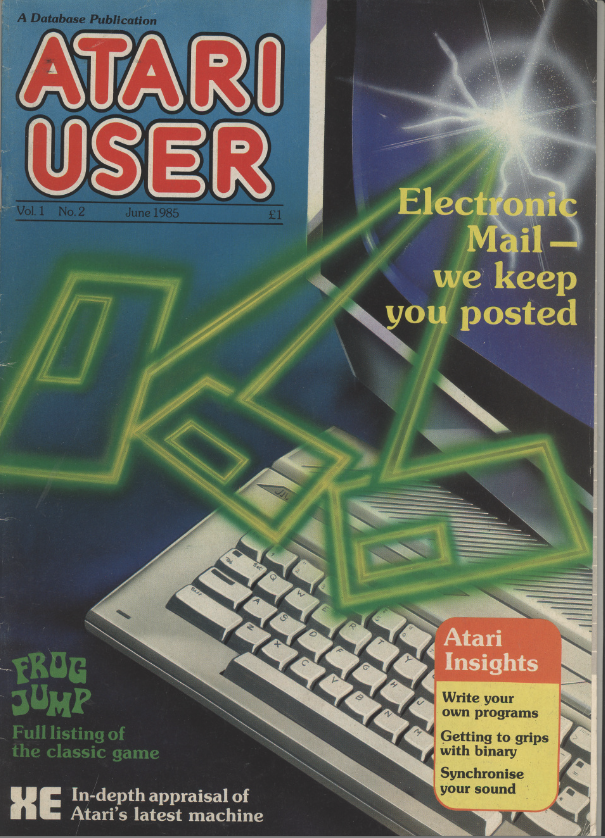

TL;DR: Atari User’s 1985 issue dives into early hacking culture, from modem-based BBS systems to the first steps into more complex networks like Prestel and Telecom Gold. Though the speeds were painfully slow (300 baud!), the excitement of connecting, downloading free software, and exploring early networks fueled a generation of hackers-to-be. Find the issue on Internet

Do you remember the day you got your first Atari? For many of us, it felt like the beginning of a grand romance. But if you flipped through Atari User magazine in 1985, you’d notice something else brewing beneath the surface: hacking—whether intentional or not.

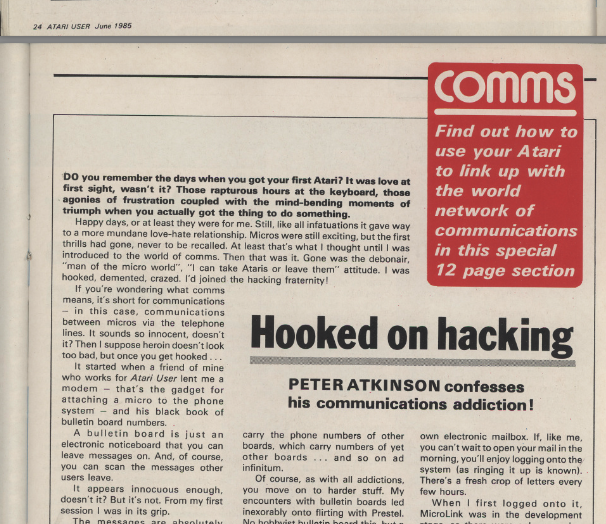

In Atari User, Volume 1, Issue 2 (June 1985), Peter Atkinson confesses his “accidental” initiation into what he calls the “hacking fraternity.” What starts off as a playful obsession with bulletin board systems (BBS) quickly spirals into full-blown modem addiction. Think of it as the original geek drug—no needles required, just a phone line and a stubborn Atari.

Hacking Before it Was Cool

Atkinson’s slippery slope into the world of hacking begins innocently enough. A friend lends him a modem (the “gateway drug” of early hackers), which allows him to connect his Atari to the phone line. And voilà—he’s suddenly part of the comms world, swapping messages on bulletin board systems.

For those of you too young to remember, BBS wasn’t some secret society of cyber masterminds—at least not yet. It was essentially a digital message board where people could leave text for others to find. But in the hands of a 1980s hacker-in-training? It was dangerously fun. People exchanged programming tips, vented about politics, or traded second-hand gadgets (and occasionally spouses, apparently). And Atkinson? He was all in.

Free Software? Sign Me Up!

One of the most humorous parts of the article is Atkinson’s glee at the free software he could download. “It’s free! Even if I’ve no need for it, I can’t resist having it,” he confesses. If you’re wondering where this free stuff was coming from, well, so were a lot of people. Many early hackers exchanged software (let’s call it what it is—pirated software) via BBS. And if that wasn’t enough, those BBSs also conveniently listed the phone numbers of other BBSs. So the cycle of obsession continued, like an endless scavenger hunt for more digital treasure.

The Hacker Spirit Takes Over

But of course, like any good addiction, the amateur tinkerer eventually graduates to harder stuff. For Atkinson, it wasn’t long before he outgrew basic BBS systems and dove into Prestel—an early nationwide commercial network—and then the almighty Telecom Gold, a sophisticated electronic mail system. He wasn’t just downloading free software anymore; he was hooked on the idea of connecting, exploring, and bending technology to his will. And with systems like Telecom Gold, things got fancy: personal electronic mailboxes, real-time chat, and message boards that made early Atari users feel like tech wizards.

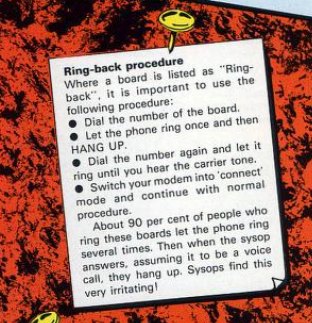

Let’s not forget that by 1985 standards, these early hackers were technically advanced. Configuring RS232 connections and making sure modems were set to the right baud rate (300 baud for BBS, 1200/75 baud for Prestel) were skills that made you the digital equivalent of a sorcerer. And for Atkinson, all this technical tinkering was simply fuel for the fire. Once he got a taste of that online world, there was no going back.

From Hobbyist to Hardcore Hacker

The tone of the article shifts from hobbyist fascination to what could only be described as “hacker mania.” Atkinson jokingly laments his transformation from a casual Atari user into a “demented, crazed” comms addict. Gone was the cool, collected tech enthusiast—replaced by someone who couldn’t resist logging in every chance he got, dialing in to check if new messages or software were available.

And that’s where it hits home: this early journey into the world of bulletin boards, modems, and message sharing was hacking in its purest, most innocent form. It wasn’t about breaking into government systems (yet); it was about pushing the boundaries of what technology could do, all while staying glued to a CRT monitor, waiting for those satisfying beeps and clicks of a successful connection.

Gold Nugget Found in a Mud Puddle: Who Knew?

Believe it or not, I managed to stumble upon a hidden gem in this article — a rare moment of clarity in a sea of questionable insights. Who would’ve thought? And to think, our DevOps heroes of 2024 still find reasons to complain!

A Note on Speed—And a Hilarious Streaming Problem

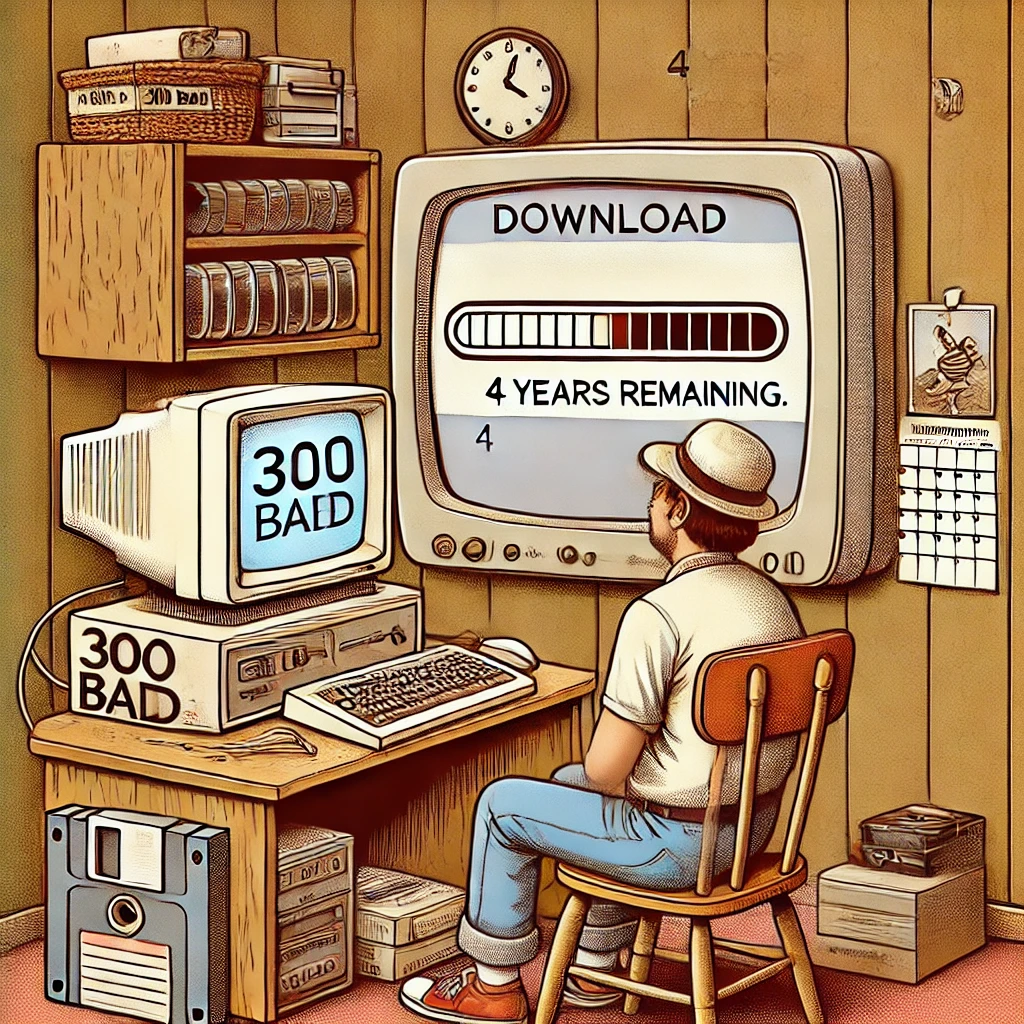

Now, for those of you reading this with fiber-optic internet and the luxury of streaming your movies in 4K, consider this: back in the 1980s, Atkinson and his fellow hackers were working with 300 baud modems for BBS and 1200/75 baud for Prestel. To put this in perspective, if you wanted to download a simple HD movie file (say, around 4.5GB), it would take roughly 34,952 hours (or about 4 years) at 300 baud. Even the faster 1200 baud connection would take a whopping 8,738 hours (about 1 year)!

Now, imagine trying to stream a movie with those speeds. You hit play, wait two days, and finally get to watch the first frame. You get up to make a cup of coffee, and by the time the second frame loads, you’ve aged a year. Now that’s what I call delayed gratification! Talk about turning “binge-watching” into “time-traveling.”

Some Things Never Change

Atkinson jokes that every modem should have come with a health warning, much like cigarette packs today. He wasn’t far off. Once you stepped into the world of early hacking, whether through BBS or commercial networks like Prestel, it was hard to step away. And while today’s hacking looks a lot different—with Wi-Fi, high-speed internet, and cloud-based everything—the spirit is still the same: curiosity, ingenuity, and a little bit of rebellion.

For those wanting to dive into the good ol’ days, you can find vintage issues of Atari User on Internet Archive. It’s a nostalgic look at when hacking wasn’t just a profession or subculture—it was a new frontier.